Benzos: Our Looming National Crisis

Drugs like Xanax were originally thought to be less dangerous

By Andrew Chamberland

When Gregory Harper awoke on April 6th, 2020, he found himself behind bars at an Austin-area jail. The 21 year old, who asked us not to use his real name, was facing multiple charges from crashing his car through a private home’s gate the night before. He’d also stolen $300 of fishing supplies from the house. Why? He had no idea.

Somewhere along the way his brand new Nissan Sentra had gone up in flames. “The seats were burned out,” he says. “It was just a black shell.

It was perhaps the craziest night of his life, but Harper doesn’t remember a thing. He’d been drinking and taken what looked to be a Xanax bar, sold by a local dealer. But the pill was fake and didn’t contain alprazolam, the drug in Xanax. Instead it contained a little-known knock-off that was much stronger.

Stories like Harper’s are increasingly common. Blackouts and overdoses from benzodiazepines – a commonly-prescribed class of sedative drugs also known as benzos – have been rising in recent years. In fact, they are now killing more Americans than ever before, almost always in combination with opioids and/or alcohol.

It is opioids that have been dominating headlines, however, leaving benzos as an incredibly severe -- yet almost-unknown -- threat.

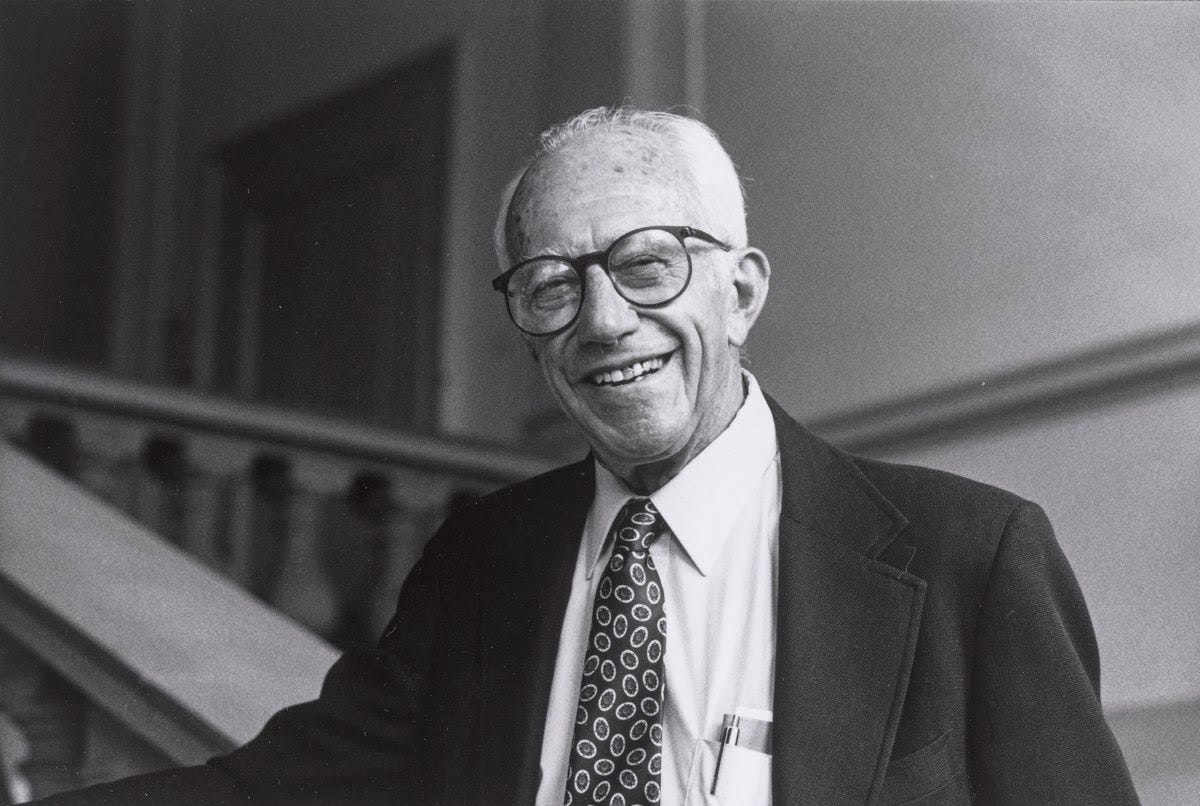

Benzodiazepines were developed in 1963 by Polish chemist Leo Sternbach. His anti-anxiety drug Valium became a sensation, growing more popular than barbiturates, the class of sedatives that killed Marilyn Monroe and Jimi Hendrix.

Benzos were believed to be safer and, in fact, when used by themselves, are almost impossible to die from. This helped Valium become a staple in medicine cabinets across the country and a fixture of American popular culture, featured in Hollywood films like Annie Hall.

Valium was followed by Klonopin, Ativan, and then, in 1981, Xanax, the first benzodiazepine granted FDA approval for panic disorder. By 2018, Americans were filling 21 million Xanax prescriptions per year.

In the meantime Xanax has also become a staple of popular culture -- particularly in rap music lyrics, cited by celebrity MCs like Lil Wayne and Future. Rapper Lil Xan even named himself after the drug, before announcing he would change his name to Diego following fellow rapper Lil Peep’s death in 2018, who had Xanax and other drugs in his system.

Other high profile benzo-related deaths include Brittany Murphy, Heath Ledger, and Mac Miller. These medications are highly abused; of the 13 percent of Americans who take them, 17% misuse them.

And yet, according to experts, the most dangerous types of benzos are not Xanax or Valium themselves, but knock-off versions. Street dealers around the country are increasingly trafficking in counterfeit pills that look exactly like legal benzos, but instead contain analogues with no history of human trials. These are known as “novel” or “designer” benzos.

While overall benzo deaths increased some 43 percent between 2019 and 2020, deaths from novel benzos increased 520%.

“They’re more potent and they’re also not regulated so you don’t really know what you’re getting,” says Dr. Anna Lembke, Chief of Stanford University’s Addiction Clinic.

In the case of Gregory Harper, he had taken clonazolam, a novel benzo that is 2.5 times stronger than Xanax and known to cause blackouts.

For the time being these novel benzos remain in a legal grey area in most states. Though they’re likely subject to the Federal Analogue Act -- which automatically schedules analogues of banned drugs -- many have not yet been explicitly banned, leading some users to believe these chemicals are not only legal, but safe.

Sold on both the dark web and the clear web, they are incredibly cheap to buy in bulk from Chinese labs. Traffickers pay as little as a few thousand dollars for a kilo and press them up on pill-pressing machines, which make them look like Xanax or other legitimate pharmaceuticals. Many novel benzos are potent at doses as low as half a milligram. Thus, one gram can be spread out over 2000 pills.

The profit margin is astronomical, and as these pills work their way through the supply chain the street dealers themselves often don’t know what they’re offering. “My guess is that most of the time the person selling it to the end-stage user has no idea what’s in it,” says Lembke.

Novel benzos are typically synthesized in labs in Eastern China. But these are not stereotypical drug operations. Unlike the Mexican cartels, Chinese traffickers are not prone to violence; rather, the majority try to operate within Chinese law.

Yet the laws are constantly shifting. In 2019, at the behest of the United States, China blanket-banned fentanyl analogues, which had been among these labs’ biggest money makers. As a result many quickly shifted to novel benzos, which remain completely legal in China.

China’s fentanyl analogue ban didn’t actually slow the spread of fentanyl in the U.S.; in fact, fentanyl is killing more people here than ever. When combined with the proliferation of fake benzos, the problem has mushroomed. Opioids and benzodiazepines -- both downers -- are often lethal in combination, slowing breathing to a stop. Some 93 percent of benzo overdose deaths in the first half of 2020 involved opioids, usually fentanyl.

It’s not easy to be optimistic about potential solutions, though increasingly-sophisticated drug-checking kits and other harm reduction methods are good first steps. As for China, the country will likely soon begin scheduling novel benzodiazepines piecemeal, which would slow their spread, as compounds like clonazolam and flualprazolam tend to be too complex (and expensive) for clandestine chemists in the U.S to manufacture.

This may not improve the American situation on the ground, however, as Chinese chemists will likely quickly shift to manufacturing different -- yet equally lethal -- drugs.

As for Gregory Harper, he will soon complete a rehab program in California, where he’s attempting to turn his life around. But for all his progress, his status remains in limbo as he awaits trial. “They’re pretty slow, the court system up there, so I’m not really sure what’s going to happen,” he says. Although he’s optimistic and ready to start fresh, the repercussions of his actions in April 2020 may continue to haunt him. All of this from a night he doesn’t even remember.