How the CIA Got American Soldiers in Vietnam Hooked on Heroin

An excerpt from the new book Narcotopia

Ben Westhoff’s note: Most people know about how the CIA turned a blind eye as cocaine from Nicaragua was trafficked into inner-city America in the 1980s, fueling the crack epidemic.

Less known is that the CIA was directly involved in another shocking drug crime: helping move heroin into Vietnam, leading directly to American soldiers getting hooked in the 1960s and 1970s. The scandal is detailed in journalist Patrick Winn’s excellent new book, Narcotopia: In Search of the Asian Drug Cartel That Survived the CIA, which is excerpted below.

Narcotopia otherwise mostly focuses on the Wa State, an autonomous narcostate contained within the borders of present-day Burma, which isn’t internationally recognized as its own country, but nonetheless has a half million people, roads, schools, etc., sustained almost entirely by meth production. I highly recommend the book.

Excerpt From Narcotopia

By Patrick Winn

THE CIA NEVER set out to entangle itself in Asia’s drug trade. This was an unintended consequence of a badly conceived plot—one that involved dropping machine guns from airplanes.

Here’s the backstory. In the early 1950s, Mao Zedong’s army purged all manner of undesirables, including Chinese enemies of communism: frontier opium traders, rich landowners, marooned Kuomintang soldiers. These targeted Chinese groups clung together, escaping death by fleeing into the wilds of Burma.

At first the Chinese exiles wandered, eating lizards and roots to survive, a rabble turning more skeletal by the day. Some did their best to avoid a Burmese ethnic group called the Wa, known to be headhunters, while others drifted into foothills. Many expected to starve in this unfamiliar land. But then salvation arrived: propeller planes whirring into view, swooping low, dropping crates hitched to parachutes. The floating boxes contained rice, bullets, and firearms. Each was a care package from the CIA. The newly created spy agency was embarking on its most ambitious mission in Asia to date.

In coordination with the Kuomintang government, displaced to the island of Taiwan, the CIA wanted to arm these communist-hating stragglers in Burma and fuse them into a mighty armed force. Then they’d send them back to China to seize the country from Mao and reestablish Kuomintang rule—so that China would, once again, belong to a US-friendly regime. This clandestine armed group in Burma, created by the CIA and the Kuomintang, went by several names, so for simplicity’s sake, I’ll call them the Exiles.

The airdrops kept coming. CIA planes stripped of all markings delivered a mishmash of firearms to the Exiles: British-made Sten submachine pistols, M1 rifles, even Thompsons, the machine gun made famous by Chicago gangsters.

Many guns were pulled from old US stockpiles, their serial numbers scratched off. The operation was top secret: only the US president and a small CIA clique knew of it.

By the spring of 1951, the Exiles were ready to cross back into their native China. They gathered along the China-Burma border and prepared for combat. Numbering in the mere thousands, they were about to face more than three hundred thousand communist troops glued to the border. The CIA naively believed the Exiles would push through and triumph. They were certain the Chinese masses, surely growing sick of Maoism, would rise up and join this fight for freedom.

This didn’t happen. When the Exile fighters rushed into China, the People’s Liberation Army shot them to bits. They ran back into Burma’s jungles, wounded and demoralized.

Over the next few years, America goaded the Exiles into several more incursions into China. Each ended catastrophically.

The CIA couldn’t accept that China was forever lost to communism, but the Exiles had to face reality: they were permanently stuck in Burma.

They made the best of it, drifting back to what many knew best: commerce. Though the Exiles continued amassing American supplies—weapons, food, medicine—as if still intending to reclaim China, they treated it as seed capital for a business venture: transforming their guerrilla force into an opium-trafficking syndicate.

Burma’s mountains contained Asia’s finest soil for poppies, but as the Exiles saw it, indigenous tribes squandered their potential by only churning out a few dozen tons of opium per year. To increase output, the Exiles turned their superior firepower on upcountry peasants. As conquerors on horseback, with new-model American machine guns, they easily strong-armed locals into farming as many poppies as the land could bear.

They mostly left the Wa alone—too hard to subjugate—so the Shan people, being most plentiful in Burma’s hills, bore the brunt of this coercion. The Exiles bought their crops for a pittance, turning them into serfs living hand to mouth.

This business expansion proved wildly successful. The Exiles boosted Burma’s opium production to five hundred tons per year: “almost a third of the world’s opium supply,” according to the CIA. Drugs were clearly the Exiles’ new raison d’être, not vanquishing communists. Yet the CIA still wouldn’t abandon them. In fact, when the Exiles needed help moving their opium to buyers in the cities, the CIA lent its airplanes to the task.

Agency-hired pilots would skitter down on dirt runways in Burma, offload guns to the Exiles, then onboard bundles of their opium. Then they’d fly to Bangkok, where purchasers, mostly CIA-supported Thai police officials, picked up bulk drug shipments right at the airport. The proceeds of these sales supercharged the Exiles’ growth. It was the first instance of CIA-contracted planes running drugs for an armed group—but hardly the last.

Over the next decade or so, the Exiles perfected their business model, assembling an opium-trading behemoth greater than their ancestors could’ve imagined. Almost all of Burma’s opium supply fell under their monopolistic control. Burma’s junta wasn’t thrilled that a US-armed drug cartel marauded through its country, but the Exiles mostly stuck to mountains beyond the military’s control. Occasional shootouts between the Exiles and Burmese patrols often ended poorly for the latter, so junta regiments tried to stay out of their path.

BY 1967, THE EXILES cartel numbered some three thousand armed men, their calves diamond hard from tromping up and down Burma’s slopes. When they weren’t on months-long smuggling runs, the men and their mules rested in secret camps strewn along the Thai-Burma border.

American spies encouraged the government of Thailand, then a US client state, to let the Exiles unofficially control the border with Burma. Asking Thailand to effectively cede territory to a drug cartel was an unusual request, but times were tumultuous, and this was no ordinary cartel. Its ranks were filled with men who reviled communism, an ideology sweeping across Southeast Asia. The United States had already invaded Vietnam to stop its spread. It wasn’t working out too well. In the countries sandwiched between Thailand and Vietnam—Laos and Cambodia—smaller communist insurgencies were heating up fast. America treated Thailand, right-wing and military run, as a firewall through which communism must never pass, lest it keep burning all the way to Burma, India, and beyond.

The United States convinced Thai leaders to let the Exiles dig in and protect that northern border. The idea was that, if communist guerrillas of any stripe dared come near it—or even popped up along dope-smuggling trails in Burma—the Exiles would crush them. They were hardy fighters with rocket-propelled grenades and .50-caliber machine guns, enough US weaponry to hold their own. Best of all, the Exiles would provide this service for free. Drug cartels don’t require outside financial backing. As for their criminality, this was something both the CIA and Thai leaders could overlook. Running drugs was unseemly, sure, but nothing was more important than containing communism.

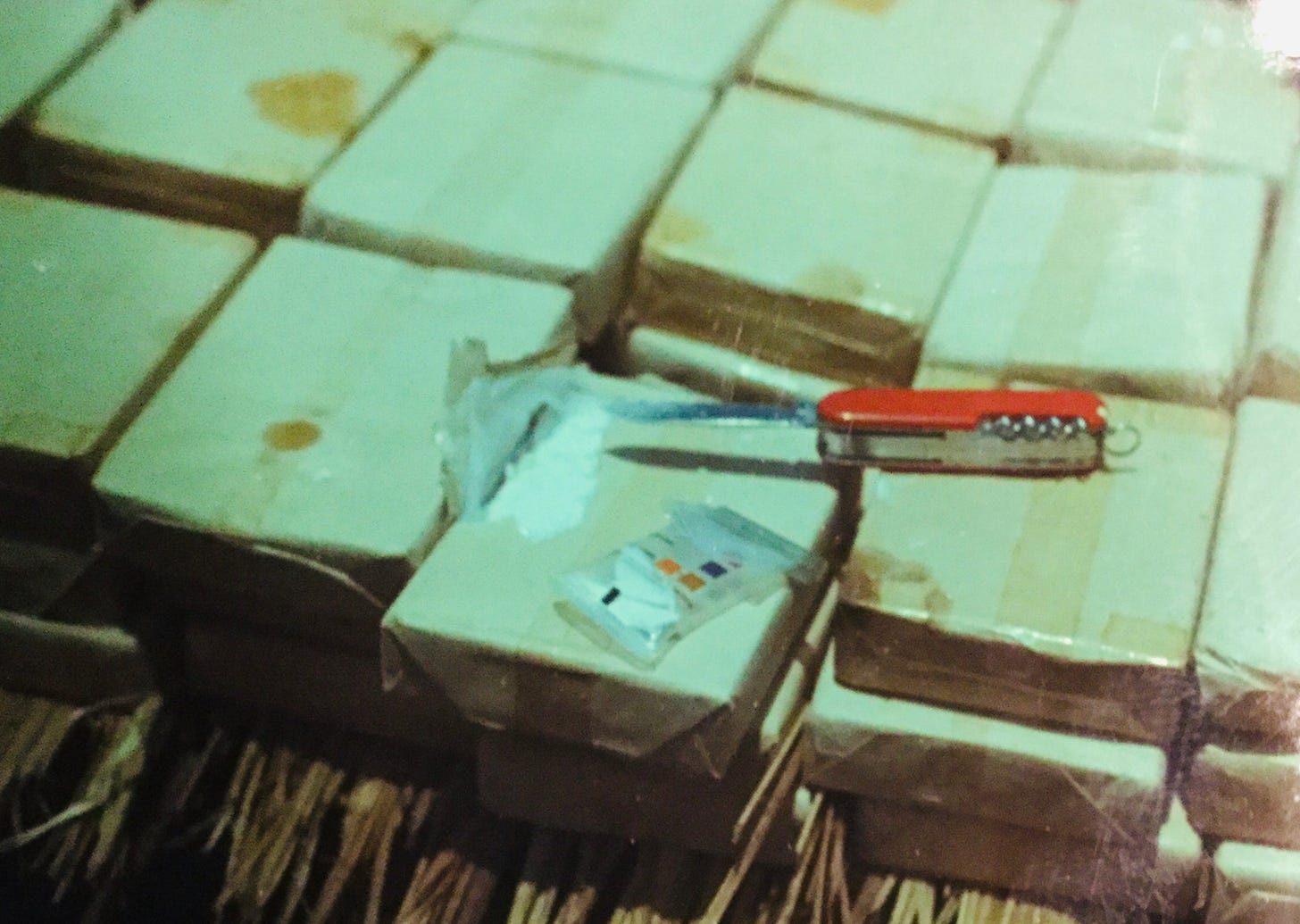

To further ingratiate the Exiles with Thai authorities, the United States nudged them into profitable partnerships. By the late 1960s, the Exiles had progressed far beyond simply peddling raw opium. They now focused on a value-added product: heroin. Hired chemists ran more than a dozen bamboo-walled refineries around their camps. The profit margins were incredible. For an outlay of $300, the Exiles could acquire ten kilos of Wa opium and synthesize it into one powdery kilo of heroin.

Wrapped in cellophane, that brick would sell for $1,000 in Bangkok. But the Thai capital was very far away, and the Exiles could hardly march heroin across the country on its mules. Once again, the Exiles needed assistance moving their wares out of the hinterlands.

Thailand’s Border Patrol Police—a CIA-created organization—stepped in to help. It owned US-supplied trucks and armored vehicles, rugged enough to drive up steep slopes. For a cut of the sale price, Thai border cops would load their trucks with Exile heroin and drive it down to Bangkok, a fourteen-hour journey. Much of the ride was made smoother by sleek highways, built by the United States to develop the country.

Thanks to corrupt Thai police, the Exiles could deliver their product without fearing arrests or seizures. Piece by piece, the infrastructure of the Golden Triangle narcotics trade clicked into place. America hadn’t planned to help construct a 650-mile-long opium pipeline, but that’s what it was. At the far end were the opium suppliers: Wa warlords. In the middle, mule caravans, drug labs, and shady cops. And at the terminus, wholesale buyers in Bangkok.

The Exiles exclusively sold heroin to one type of customer: Bangkok’s ethnic Chinese, a community that had migrated long before, establishing themselves as urban merchants. They were high-society types, “respected members of their communities,” according to CIA files, viewing themselves as “businessmen first and criminals second, if at all.” Chinese-Thai families ran export businesses, shipping everything from pineapples to car parts, so they already owned warehouses, trucks, and boats—everything needed to smuggle a kilo or ten to whichever market fetched the best price.

And in the late 1960s, the hottest market for heroin was South Vietnam. As the US-Vietnam War intensified, draftees kept flooding in, until half a million young men from the world’s most prosperous country were plopped down in a jungle nightmare. Terror and trauma ran rampant. Many troops craved chemical escape. Without intending to, the Pentagon created the perfect customers for heroin produced in the nearby Golden Triangle—all while the CIA helped sustain supply chains that fed soldiers’ addictions.

GIs didn’t think they were rich, but on an $80 monthly salary, they were far wealthier than the region’s peasants, who ate whatever they grew and could never afford a drug habit. As the war dragged on, according to some estimates, as many as one in six US troops in Vietnam were using heroin.

Americans back home had no idea they were subsidizing Southeast Asia’s dope trade. US citizens’ salaries got taxed to pay soldiers’ wages. GIs took that money and paid Vietnamese dealers. The Vietnamese dealers in turn paid the ethnic Thai-Chinese distributors in Bangkok. And they told the Exiles to keep the product coming.

The CIA coldly observed this flux of dollars and heroin, in which it was complicit, but did nothing to stop it. The agency could hardly claim ignorance. In secret memos, it noted that the Exiles were building new drug labs for a specific purpose: meeting a “sharp increase in demand for heroin by US forces in South Vietnam.”

What on earth could justify the CIA propping up a cartel whose heroin shot into American soldiers’ veins? Behind every CIA scandal, there is always some big-picture justification. In this case, it was communism—specifically communist China. The CIA didn’t just want the Exiles watching out for communist uprisings in the Golden Triangle. That was only one of their responsibilities. The agency also needed them to go much deeper, probing their native homeland: China, a country controlling nearly 20 percent of all human life, plus a growing arsenal of nuclear bombs.