Credit: Howard Huang

The Hip-Hop 25 counts down the 25 greatest rap artists in history, as part of Ben Westhoff’s newsletter Drugs and Hip-Hop. Get your paid subscription now before it all goes behind a paywall.

We live in so many different countries, bundled together and marketed as America. Accents, dispositions, landscapes, politics, the ways we clog our arteries and cloud our consciousness, the things we accept as fact; they change from region to region. Hip-hop is like that too. Unlike with other music genres, a trained ear can immediately recognize where performers are based. Slow and screwed from Houston, slang-ridden from the Yay Area, frenetic from Miami, verbose from Brooklyn, slurrred from St. Louis.

That’s how it used to be, anyway. Now everything’s merged together. Maybe it’s no coincidence that regional distinctions began melting away with the rise of Nicki Minaj about eleven years ago. As she played with alter egos like Harajuku Barbie, Nicki Lewinski, Roman Zolanski, Nicki Hendrix, and Nicki Teresa (as in, “Mother”), she also toyed with her patois, speaking and rapping with accents from New York, the Caribbean, Japan, and England. It came naturally. Born Onika Maraj in Trinidad, she grew up in Queens and, when her career blossomed, moved from one hip-hop epicenter to another — Atlanta to Los Angeles to Miami.

"When I started rapping, people were trying to make me like the typical New York rapper, but I'm not that," she told Billboard. "No disrespect to New York rappers, but I don't want people to hear me and know exactly where I'm from."

This helped broaden her appeal, but caused confused internet souls to search for answers about her identity, ethnicity, and sexuality. (Indian? Bisexual?) They would learn she’s a lady of the world, crediting inspiration for her style to everyone from Foxy Brown to Larry David (“he has a lot of sarcasm.”) When, in 2010, she was invited onto her biggest showcase to date, Kanye West’s “Monster,” she painted her nails purple, popped in a pair of fangs, and took a deep breath. What came out of her mouth K.O.’ed the era’s top rappers in one punch.

In early 2012, Jon Caramanica of The New York Times called her “the most influential female rapper of all time.” Her career had barely begun.

There was trauma from a young age. After living in Trinidad with her grandmother until age five, she moved in with her parents in Queens. They were both gospel singers, but her father had substance abuse issues, and beat her mother repeatedly. Minaj said her father once tried to set fire to their home. She told Rolling Stone:

When I first came to America I would go in my room and kneel down at the foot of my bed and pray that God would make me rich so that I could take care of my mother. Because I always felt like if I took care of my mother, my mother wouldn’t have to stay with my father, and he was the one, at that time, that was bringing us pain.

She studied acting at Manhattan’s LaGuardia High — the Fame school — and after graduating worked odd jobs and wrote rhymes in the kitchen during her waitress shifts at Red Lobster. She was driven, but couldn’t help herself from tangling with customers, one time chasing a diner out of the restaurant who had taken her pen so she could flick her off.

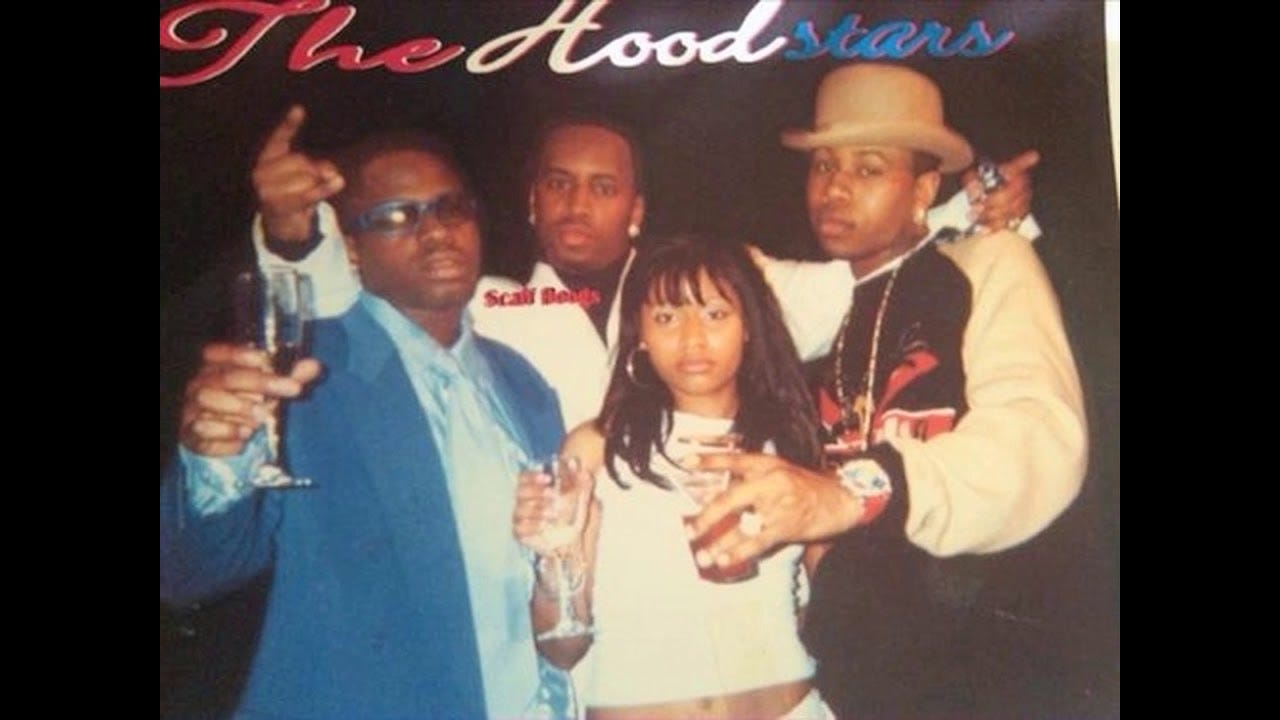

She worked with a group called The Hoodstars, but wouldn’t gain traction until she began performing solo. A producer named Big Fendi nicknamed her Nicki Minaj, and her early persona was heavily sexualized, in the vein of Lil Kim. Her debut mixtape Playtime Is Over, from 2007, begins with a slurping sound. She imparts:

I can't come to the phone right now, because I'm sitting on your favorite rapper's face.

In these days rappers auditioned for fans by rhyming over the hot beats of the day, and Minaj was clearly more talented than the tracks’ original authors. Many in the music industry took notice. I have received hundreds of publicists’ emails about Nicki Minaj over the years; the first came in 2008, though it incorrectly spelled her name, “Nikki Menaj.” Soon after I received a link to a remix she was on, but it was only available on MySpace.

She’d already been discovered by Lil Wayne, who was in New York thumbing through street DVDs when he found her on a series called On the Come Up. Within four bars he knew she was the truth. She was the first signing to his new label Young Money, and he then signed Drake as well.*

*Whom would you include on a Mount Rushmore of the best hip-hop A&Rs? Carving faces onto a mountain is time-consuming and laborious, so choose wisely. I’d include Wayne. Baby too. Dan Charnas has them at number eight on this list.

Nicki gelled with the crew immediately, and joined Wayne on his Best Rapper Alive tour in 2007. On a stop in Columbus, Ohio she met the opening act, an up-and-coming trap rapper from Atlanta named Gucci Mane, who described their encounter in his memoir:

I saw this pretty girl get off Wayne’s bus and start running toward us. She was small, no taller than 5’2”, but right away I saw a big personality.

They exchanged numbers and Nicki began commuting in her white BMW to Atlanta to make music, with Gucci putting her up in hotels until she found her own place. She was quickly out in front not just with Young Money but with Gucci’s crew as well. I’d never heard of anything like that happening. Music labels and rap cliques tend to be territorial, yet somehow Wayne and Gucci simultaneously mentored her. She told Shaheem Reid:

Gucci is real fast. He'll force me, like, 'No, no, no. You're taking too long.' Wayne, we'll have more of a laid-back situation. He'll give me time to tweak a little more. But they both teach me a lot — they both a have a crazy work ethic. Wayne is my sensei. That's what I call him. He calls me his ninja. 'Ninja Nicki.' "

If you strain you can pick up both rappers’ influence, but really she already had her own style, both old-school and modern, delicate and aggressive. Her appearance on the 2009 remix to Yo Gotti’s “5 Star Chick” was her first time on a video set. The song also features Gucci Mane and Trina, and for the first 3/4 of the video Minaj is basically set dressing. You could be forgiven for thinking the song is over when she finally comes on at the 3:15 mark. "I just had a epiphany / I need to go to Tiffany's,” she begins (amazing line). “I was in the chair, I was gluin' my weave in / When you hit the stage, they was booin' and leavin'.” Ha!

Can you imagine what it would be like to walk into a situation like that, with established rappers, and fairly codified gender roles you’re expected to conform to? Making the story even crazier is that Minaj was sorely lacking in self-confidence at the time. Her manager Debra Antney (whom Nicki met through Gucci) told The New York Times Magazine:

Nicki was the timidest little girl you’d ever want to see in your life — she was so broken up, but she was so determined, all in one breath….I used to have to scream at her: “You’re not going to sit here and cry, you’re not going to let nobody shut you down, that’s what you’re not going to do.'“

Debra Antney is Waka Flocka Flame’s mother, a Queens native who transformed herself into a southern rap industry titan. She’s a force of nature, someone whom I’ve had the pleasure of being shouted at during an interview. Without any substantial music business experience, Antney pushed her way into the industry and took over for a time, managing some of the biggest artists of the era. She wasn’t afraid to get her hands dirty, once showing up at an Atlanta trap house where Gucci Mane was dealing drugs to tell him he was throwing his life away.

Antney’s chutzpah rubbed off on Minaj, and she soon fully came into her confidence. It helped that Young Money’s 2009 showcase “Bedrock” featured in heavy radio rotation.*

*I was going to make fun of this song but I’ve got to be real and just admit that it’s awesome and I love it.

Along with a bevvy of other female MCs she appeared on Ludacris’ album Battle of the Sexes (that’s make-fun-of-able) and then “Monster.”

Let’s talk about “Monster” for a second, and what makes her verse so special. People sometimes compare hip-hop to poetry. Really, hip-hop is more complex. More important than the words themselves is the delivery. Rapping a verse requires creating a separate rhythm that complements (or sometimes clashes with) the beat. You need both proficiency and style. On “Monster” Jay-Z has the former, which Kanye and Rick Ross exhibit the latter. But Nicki is better and more interesting than all of them. She inhabits a pair of personalities, one the sadist, one the masochist, creating drama when the alter egos argue. She varies her speed like a running back, slowing down for the juke and then blowing past. Her verse is technically complicated, with all sorts of internal rhymes, but you’re left with the sheer magnitude of her personality.

Her debut album hadn’t even dropped. Music by now had become free and the idea, as Wayne demonstrated with Tha Carter III, was to entice fans with tons of gratis mixtapes before finally charging them for the album. I’m not sure why that worked; probably, for most artists it didn’t, but it did for Pink Friday. Shortly before its release, Minaj had seven songs in the Billboard Top 100 at the same time. Pink Friday hit number one.

It wasn’t the best, but the first song is called “I’m the Best,” and the whole thing was a sort of fait accompli, because she was so good, and because, despite the album’s lesser moments (“Put your number twos in the air if you did it on’em”) the highs were so much higher than most anything else out. Because she had already won over the rap industry gatekeepers, the best-known artists, and the critics, she focused on winning over a broad base of fans, not the hip-hop nerds but the young girls and the teenage boys and the casual radio listeners. This involved not just music but lots of modeling and photo shoots, for which she also exhibited intuition, style, and flare.

She accelerated this strategy with 2012’s Pink Friday: Roman Reloaded, her competition no longer other rappers but Lady Gaga, Taylor Swift, Katy Perry and the other women who ruled the charts. The rock music landscape has long been cluttered by disgruntled fans and think-piece writers who argue that musicians shouldn’t be in it for the money — as if earning a living performing your art is somehow dishonorable — and hip-hop has this too. These maniacs started coming out of the woodwork with the release of Nicki’s massive single “Starships.”

A prominent DJ at New York radio station Hot 97 was so offended by the song that he called her out for it on-stage, right before she was about to perform at the station’s Summer Jam concert. She promptly canceled her performance.

Is “Starships” the greatest? No. It employs the then-in-vogue radio formula pairing fast rapping with soaring, sung hooks, which worked for Eminem and Rihanna and sounded similar to other productions from RedOne and Dr. Luke. But it’s a great pop song, one that didn’t diminish hip-hop at all, as the DJ seemed to be suggesting. Quite the contrary. Hip-hop is the ultimate big tent genre; there’s room for everyone, and every unlikely fan that Minaj invited under was likely to stick around and go deeper. Besides, why should she continue trying try to please these haters? As she told Rolling Stone:

I had so much going against me in the beginning: being black, being a woman, being a female rapper. No matter how many times I get on a track with everyone’s favorite M.C. and hold my own, the culture never seems to want to give me my props as an M.C., as a lyricist, as a writer. I got to prove myself a hundred times, whereas the guys that came in around the same time as I did, they were given the titles so much quicker without anybody second-guessing.

She received more flack following her 2014 release The Pinkprint, for which she portrayed the title character of Sir Mix-a-Lot’s “Baby Got Back” for her own version, called “Anaconda.” The feminist scholar bell hooks was unimpressed. ‘‘This shit is boring,” she said. “What does it mean? Is there something that I’m missing that’s happening here?’’

While intellectuals debated her impact on society, Minaj was expanding her reach (“Anaconda” has nearly a billion views) while still demolishing verses (Complex picked her as 2014’s “Best Rapper Alive”) and living out her dreams, hiring a soccer team’s worth of assistants to help her realize her global ambitions of music, fashion, and commercial advertising dominance.

“I am stunned by the number of people Minaj has at her service,” wrote Roxane Gay. “I marvel at the sublime luxury of basically having a human closet.” From The New York Times Magazine in 2015:

In the last 24 hours, she had poured herself into a nude mesh Alexander Wang dress that the most party-hearty 19-year-old would choose only as a beach cover-up; changed to a fire-engine-red two-piece zip-up suit for Wang’s after-party; danced at Jay-Z’s 40/40 Club in the Flatiron district for hours; hit the recording studio with her boyfriend, the Philadelphia rapper Meek Mill; then, finally, crawled into bed in the hotel on the Upper West Side at 7 a.m.

Controversy followed her; there were back-and-forths with Taylor Swift and Miley Cyrus, and she was caught in the middle of the beef between Meek Mill and Minaj’s BFF/labelmate, Drake. When she and Mill broke up, they were publicly nasty toward each other. She was an American Idol judge and then left. The New York Times Magazine profile ends with the writer asking Minaj if she “thrives” on such drama, to which Minaj gave her such an incredible dressing down that the writer basically thanked her.

She’d come a long way from the timid young woman Debra Antney described, and had become fully determined never to let anyone shut her down. Her 2018 follow-up Queen went platinum in an era when nobody went platinum anymore. (I love “"Chun Swae.") She said whatever the hell she wanted, criticizing Trump for immigration policy, but praising him for being “funny as hell” on Celebrity Apprentice.

More than anything, though, she just kept working, kept making hot songs, landing more Billboard Hot 100 tracks than any female artist in history, passing Aretha Franklin. What kept her going? The glory of pleasing fans and performing her craft at the highest level, but also an insistence on independence that she has maintained since childhood.

Since I was 15, I came out of one relationship and went into another relationship. In my relationships, I’ve been told, “You don’t have to work that much.” But I can’t stop working, because it’s bigger than work to me. It’s having a purpose outside any man.

Hip-hop didn’t change her; she changed hip-hop. She offered the culture to the world, and millions took her up on the offer. It was to her benefit and their benefit and all of our benefit. Who would want to live in a world without Nicki Minaj? Not I. In fact, I can’t even imagine one.

Next up: #24 Beastie Boys.

The Hip-Hop 25 counts down the 25 greatest rap artists in history, as part of Ben Westhoff’s newsletter Drugs and Hip-Hop. Get your paid subscription now before it all goes behind a paywall.