This is a rare free post from Ben Westhoff’s newsletter Drugs + Hip-Hop, which includes The Hip-Hop 25, counting down the 25 greatest rap artists in history.

For a while Elvis’ hips were enough, but by the 1990s it had become difficult to shock people. Taboos were being violated left and right. You had Woody Allen and Soon Yi, Dennis Rodman claiming to marry himself, and the president committing sexual acts in the oval office (and seeing his approval ratings rise).

It was a strange time, when the sexual revolution had matured, and artists were not just allowed to be shocking, but expected to be.

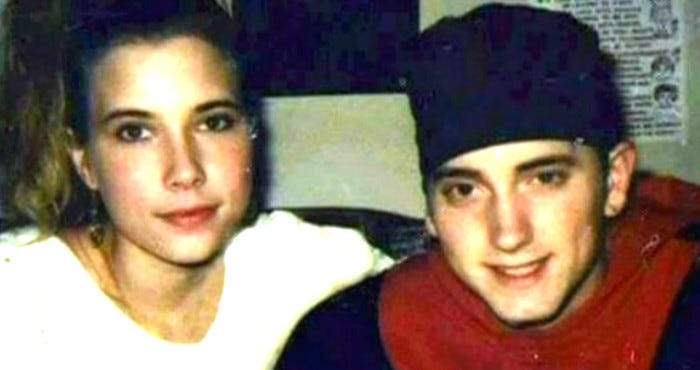

Onto this stage jumped Eminem, hair peroxided, tripping on mushrooms, rapping about drugging underage girls, raping his mother, and dumping his wife’s body in a lake while his daughter watched. There were howls of protest, but no real, successful campaigns to suppress his music.

Yet it turned out the shock value wasn’t key to his appeal. Even being white wasn’t a golden ticket. His real trick was bottling youthful angst. He spoke for those not just neglected by the economy, but currently stressed out by people in their lives: bullies, bosses, co-parents of their children.

Eminem was one of those people. Anyone could tell. He kept repeating that he didn’t give a fuck, not because it was true, but because he was trying to convince himself of the opposite.

The only way to deal with a life this bleak was to pretend the indignities didn’t matter. Indifference was a suit of armor, one which fit Shady’s nation.

Still, no one could have guessed that his brand of high-pitched invective would galvanize a generation.

Who could have known that such a caustic, mesmerizing, ugly, transcendent body of work would sell better than almost any music ever?

Born in St. Joseph, Missouri, Marshall Mathers came up in the nearby small town of Savannah, on the western edge of the state, near the Kansas and Nebraska borders.

St. Joseph is where Jesse James was killed, in 1882 in his own home, shot by a man seeking a reward offered by the governor. Mathers would namecheck James in songs, and see himself as a kindred spirit.

Eminem’s childhood story has often been told: An absent father, a harried mother, and rebellious uncles who took him to the gun range to shoot AK-47s. His uncle Todd killed a man, and when he got out of prison killed himself.

His uncle Ronnie (about the same age as Marshall) instilled in his nephew a love of hip-hop and carried with him two boomboxes, one to play the beat, and another to record himself rapping. Ronnie committed suicide too.

At a young age Mathers’ family moved to Detroit. His childhood was a blur of new neighborhoods, new schools (some operating out of trailers), and new friends. From his memoir, The Way I Am:

Whether it was a white or black or mixed community that I lived in, I was always poor. Always. Welfare cheese, Farina, powdered milk — the whole nine yards…The worst part about the way I grew up was that I never had a real home.

When he was nine an older kid beat him up in the elementary school bathroom. He bled out of his ear, and later described the experience in his song “Brain Damage.”

He banged my head against the urinal 'til he broke my nose

Soaked my clothes in blood, grabbed me and choked my throat

I tried to plead and tell him, “We shouldn't beef”

But he just wouldn't leave, he kept chokin' me and I couldn't breathe

Mathers dropped out of school in ninth grade, and says he’s almost never read a full book. As a teenager he went from one low-wage job to another, and in his early twenties had a daughter with his girlfriend Kim Scott. “Do you know how many hours it takes working as a cook to earn enough money to buy a box of diapers?” he asks in his memoir.

As Eminem, he’d go on to diss other white rappers — Vanilla Ice, Insane Clown Posse, Cage — but he drew early inspiration from the Beastie Boys, partly from their stage show with the giant hydraulic penis, partly because they were just being themselves. On a track he used the n-word to insult a Black ex-girlfriend, which later came back to haunt him.

It was his friend Proof who encouraged him to pursue rap, and provided him access. He’d smuggle Marshall into his high school and hustle other kids, winning twenties from students who didn’t think the white boy could battle. They graduated to a club called the Hip-Hop Shop, where Mathers built his self-confidence winning battles in front of sweaty crowds, as depicted in 8 Mile.

They worked at Little Caesars together, but Proof quit to pursue his hip-hop dreams. “Everybody swore he was going to be the first solo rapper to really make it out of Detroit,” wrote Mathers. In the meantime they formed a crew called D12, the Dirty Dozen, which was supposed to be their answer to the Wu-Tang Clan, though it only rallied six members.

They pushed each other to say the wildest, most controversial shit they could come up with. They swore that whoever made it out first would come back for the others.*

*Mathers kept his word, and D12’s debut Devil’s Night, released two days after 9/11, went platinum. Their follow up, 2004’s D12 World, went double platinum.

Proof encouraged each member to have an alias, and thus the Slim Shady concept was born. While “Eminem” was the technically-proficient mic-slayer, “Slim Shady” was the white trash wild card.

Mathers released his 1996 debut Infinite independently, and it didn’t go anywhere. A year later he dropped the Slim Shady EP, which featured signature songs like “Just Don’t Give a Fuck.” (Check the Luniz remix above if you haven’t.)

If he sounded like someone with deep emotional problems and nothing to lose, well, he was. He talked shit about everyone, including himself.

Extortion, snortin', supportin' abortion

Pathological liar, blowin' shit out of proportion

The looniest, zaniest, spontaneous, sporadic

Impulsive thinker, compulsive drinker, addict

Shitting on oneself in earnest just wasn’t something rappers did. But it was “Just the Two Of Us” that surpassed the high ‘90s bar of the truly shocking, with its brutal revenge fantasy about the mother of his child.

Don't worry about that little boo-boo on her throat

It's just a little scratch - it don't hurt, her was eating

Dinner while you were sleeping and spilled ketchup on her shirt

Mama's messy isn't she? We'll let her wash off in the water

That he was speaking to his daughter Hailie in the song — and using her real name — made it even more insane. He’d use Kim’s actual name in similarly brutal tracks, like “97 Bonnie & Clyde.” He told Rolling Stone:

I lied to Kim and told her I was taking Hailie to Chuck E. Cheese that day. But I took her to the studio. When she found out I used our daughter to write a song about killing her, she fucking blew. We had just got back together for a couple of weeks. Then I played her the song, and she bugged the fuck out.

Still, they would marry in 1999. “The way I’d explain it to Kim is that this is how I was feeling at the moment,” he said in his memoir. “So she wouldn’t really put up a fight about putting the songs out.” The eventually divorced twice; Kim occasionally speaks out in the press against him.

When his girls were old enough to understand, Mathers vowed to explain “that when Daddy would get mad at Mom, Daddy would make a song, and that’s how I vented.”

This doesn’t seem like a good answer. But, somehow, in a decade that kicked off with American Psycho, mutilating women’s bodies was at the forefront of mass entertainment.

Though he had begun receiving invitations to play shows, Eminem continued struggling into his later 20s. His window was closing.

He nearly won rap battles at Scribble Jam and the Rap Olympics, but came up just short. After the finals of the latter contest in L.A. in 1997, an assistant from Jimmy Iovine’s office asked for a demo, and Eminem handed it over, not expecting much.

By now Jimmy Iovine and Dr. Dre were attached at the hip. Iovine had rescued Dre from the gangster nightmare that was Death Row Records, while Dre saved Iovine from permanent obsolescence as a classic rock producer.

The success of Dre’s 1992 album The Chronic had cemented their bromance, but his follow-up Dr. Dre Presents the Aftermath tanked. Desperate for a hit, Dre needed a new artist to mold.

Upon hearing Eminem’s demo he called a meeting. Mathers showed up in a “bright yellow fucking sweatsuit,” Dre remembered, and they soon got into the studio together.

Dre played him the “My Name Is” beat, and Eminem immediately came up with the hook, singing: “Hi, My Name Is” in his comical register.

This was a true synergy of rap genius; Dre knew exactly what would work, and Eminem delivered. Together, Dre understood, they would be the ultimate package: controversial but marketable, able to win over both Black and white, the underground and the mainstream.

Soon afterwards Mathers had a wild night on ecstasy, randomly busting out a bottle of peroxide. “I had no idea what I was doing with those chemicals,” he said, but Dre and Iovine loved his new, blond look. Said the latter: “This is the identity we’ve been looking for the whole time.”

Eminem now had the stuff of dreams: A label, a famous producer, and a spot on the release date calendar.

But still. This was, by now, his third time around, and he and Kim had recently been evicted. Who knew if things would actually be any different this time.

If you haven’t listened to The Slim Shady LP recently, it’s well worth it, even if the pop culture references have aged poorly and the gratuitous lines from “My Name Is” and “Guilty Conscience” don’t hold up.

What does hold up is the angst. If you listen closely, the depth of Mathers’ misery is clear — it’s un-fakable. This is a guy who feels alone in the world.

What are friends?

Friends are people that you think are your friends

But they really your enemies, with secret identities

And disguises, to hide they true colors

In an era of manufactured rage, tracks like “Brian Damage” were the real deal.

“Rock Bottom,” meanwhile, contains brutal descriptions of life in poverty.

Livin' in this house with no furnace, unfurnished

And I'm sick of workin' dead-end jobs with lame pay

And I'm tired of being hired and fired the same day

But fuck it, if you know the rules to the game, play

You wanted to hear a marginalized voice? This was it. Long before the Trump-era thinkpieces about disaffected white people, Eminem had them in his corner, co-mingling with traditional hip-hop fans who recognized his incredible skillset.

The Slim Shady LP won the Grammy for best rap album and sold four million copies. Mathers bought a mansion. Never mind that it was across the street from a trailer park.

Now he had more than he’d ever wanted. In fact, too much. People bothered him on planes while he tried to sleep. They snapped photos of his daughter. A guy kissed Kim, so Mathers pistol-whipped him. His beef escalated with Insane Clown Posse. His mother sued him. Other family members came out of the woodwork, asking for money.

Crazily, his ascent had barely begun.

What makes “Kill You,” the second track off Eminem’s 2000 sophomore album, The Marshall Mathers LP, so terrifying?

For one thing, he’s saying he’s going to kill YOU, the listener. That’s unsettling. Then there are Dre's silences. We only get a second of the keyboard flourish before it’s abruptly yanked away. You almost never hear dead air in pop music, and the fact that half the track is nothingness creates an unhinged atmosphere.

But while “Kill You” offers a slasher-movie thrill, it doesn’t come close to the existential horror of “Stan,” which is built on a snippet from “Thank You” by British chanteuse Dido.

“Stan” is a complicated story told over an extended period of time, through various mediums (letters, a real-life meeting, a cassette recording, a news account) and two separate narrators.

Yet it flows seamlessly. The fan’s copycat murder-suicide plays out like an Eminem song, to incredibly eerie effect.

It dawns on you that there must be real-life fans like Stan out there. You can tell from the anguish in Mathers’ voice. He has clearly met a Stan, someone nearing breakdown, desperate to make somebody else pay for their pain. Maybe he is him.

“Stan” is a masterpiece, the pinnacle of Mathers’ career. Elton John co-signed the track, looking past the rappers’ homophobic lyrics to duet at the Grammys, surely a top five moment in the event’s history.

The Marshall Mathers LP sold a million and three-quarters in its first week, depositing Eminem at the forefront of the popular consciousness, where he has remained for the better part of two decades.

There were shows where the people were so loud that we couldn’t rap for 10 minutes. I remember this show in Oslo where the crowd went nuts, and I just felt like my life was a dream that was so good that I would wake up from it, realize that my real life sucked, then not know how to handle the harsh reality.

As I understand it, 8 Mile is a marker separating poor Black people from poor white people in Detroit. (At least it was at one point; they even built a literal wall.) For the eponymous film, Mathers helped re-create the atmosphere of the Hip-Hop Shop and insisted on actually filming in Detroit.*

*As a rust belt fan I’m grateful for this, although the show Detroiters is more fun.

During the filming of 8 Mile, Mathers was rehearing, babysitting his girls, and recording music, all at the same time. He wrote “Lose Yourself” on set, which is basically our generation’s “Eye of the Tiger.”

He began taking Ambien, eventually becoming hooked not just on sleeping pills, but on opioids and benzodiazepines, which can be lethal in combination.

On April 11, 2006, his long-time friend Proof was fatally shot, along with another man, at an after-hours club along 8 Mile. The circumstances were disputed; no one was charged, but Mathers was devastated.

I have never felt so much pain in my life.

In late 2007 he suffered a methadone overdose. Though known as an addiction medication, methadone is actually a potent opioid in itself, killing thousands of people per year. Truth be told it’s a small miracle he made it through alive; luckily his habit preceded fentanyl, or he may have found the same fate as Prince, Tom Petty, and Juice Wrld.

Which brings us to “Not Afraid,” his 2010 recovery anthem chronicling his descent and rebirth, which invites others to make similarly tough choices. Maybe it’s the recovery anthem; I can only imagine how many millions of people suffering from opioid use disorder — or meth addiction, or alcoholism, or abusive relationships — have found inspiration in this song.

Some of the rhymes are corny, but the chorus gets me every time. It’s a classic example of using your fame to make the world a better place.

This essay is already too long, so let’s do bullet points:

50 Cent: Eminem co-signed him and co-produced Get Rich or Die Trying, one of the fifty best rap albums ever. 50 Cent, Eminem, and Dr. Dre went out of their ways to piss everyone off, so their takeover felt pretty subversive, although when they all-three collaborated it wasn’t much.

Rihanna: Eminem’s catalog has such depth that I haven’t even mentioned some of my favorites, including “Forgot About Dre,” “Hailie’s Song,” “Renegade,” and “Like Toy Soldiers.” I’m also a sucker for most of his Rihanna collaborations, particularly “The Monster.” They’re great together, just not live. From my 2014 review of their joint concert at the Rose Bowl:

Rihanna rose out of the stage's floor, clad in what resembled a black-and-yellow leather Zubaz outfit over a crop-top. Eminem was tied to a gurney, Hannibal Lecter-style. Thus began two-and-a-half hours of lip synching.

Sales: Eminem is the best-selling rap artist of all time, by a lot, despite his career transpiring almost entirely in the post-Napster era. Think about that. At one point people basically stopped buying CDs from every artist except him. Since the millennium, in pop music generally, only Taylor Swift has come remotely close.

Political activism: When musicians support Democrats it usually feels pretty perfunctory, but considering Eminem’s get-’er-done fanbase, I was pretty impressed by his blitzkrieg against Trump. Who knows? Maybe it helped tip Michigan.*

*Best YouTube comment on the video above: “I bet donald trumps kids play this song whenever they’re grounded.”

It’s rare that an Eminem rhyme resonates with me these days, but I don’t think we’re quite done with Marshall Mathers. Many rappers peak in cultural relevance after they retire, and Eminem is still selling.

His best songs transcend era. Not the shocking ones, but the ones where he expresses how it feels to feel. He encapsulates that which drives us to the edge of the cliff, and sometimes over, the disenchantment and cynicism, the resentment and jealousy.

We’re not alone in our bitterness. Eminem shows us that. Somehow — and I can’t explain why — understanding this helps make the bitterness easier to live with.

This is a rare free post from Ben Westhoff’s newsletter Drugs + Hip-Hop, which includes The Hip-Hop 25, counting down the 25 greatest rap artists in history.

Another great essay! I learned a lot. Kind of disappointed that you're not a fan of Crack a Bottle ;). Reading about Eminem brought back more memories than I anticipated, from learning English by reading lyrics on the back of The Eminem Show CD booklet, watching 8 Mile and too much MTV as a teen, to finally moving to Detroit for a year. While I was in the metro Detroit area, I noticed that they had a tradition of playing an Eminem song on the radio every single day at 5 pm.